Prashant Patil

Prashant Patil 2021

12 February – 13 March, 2021

Opening 12 February, 6 p.m.

Prashant Shashikant Patil is the third CIMA award winner. A young artist belonging to the semi urban outskirts of Maharashtra, Prashant completed his M.F.A. from Kalabhavan, Santiniketan. We are indeed fortunate to discover an artist of Patil’s calibre. Possibly, we would have missed him, had it not been for the meticulous scrutiny and evaluation by the illustrious jury of CIMA awards. I am personally grateful to each and every member of the 25 strong jury, who shortlisted and finally awarded him.

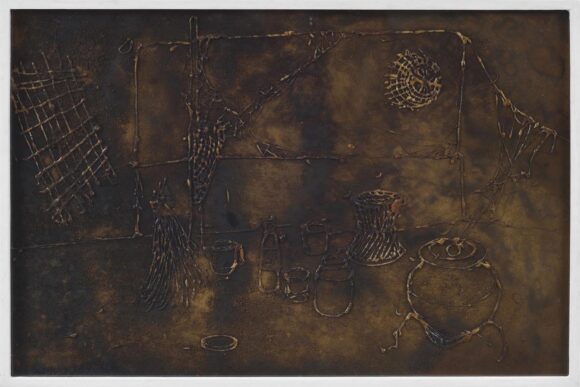

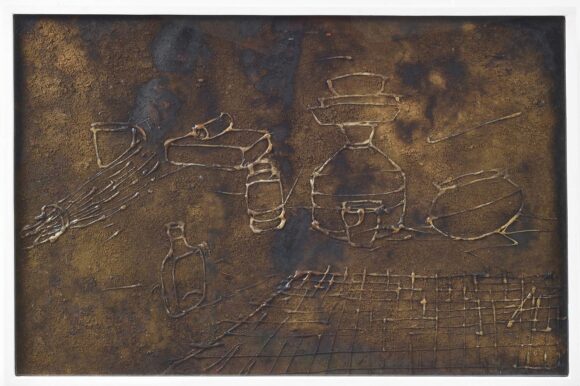

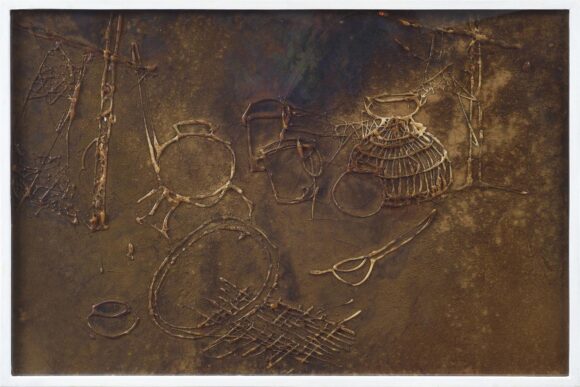

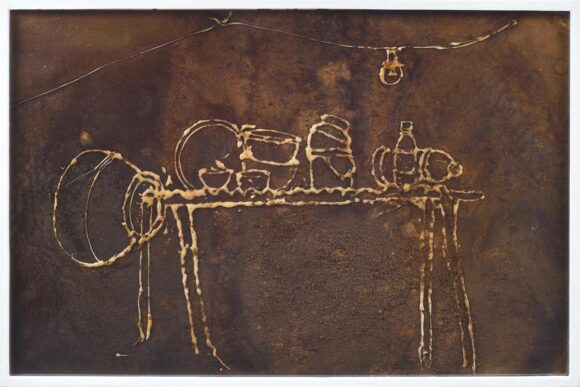

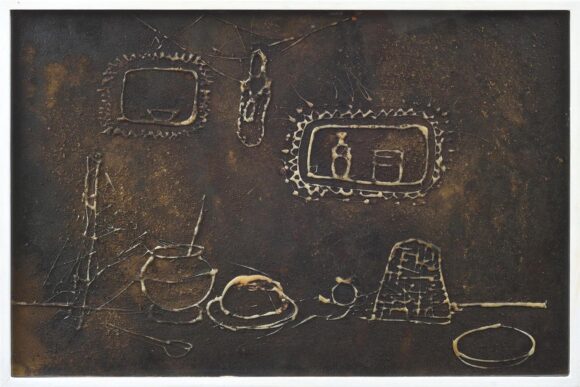

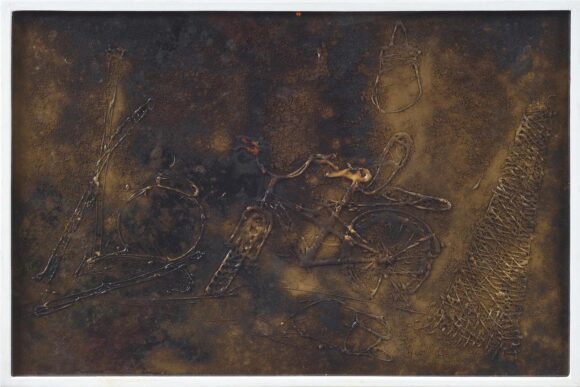

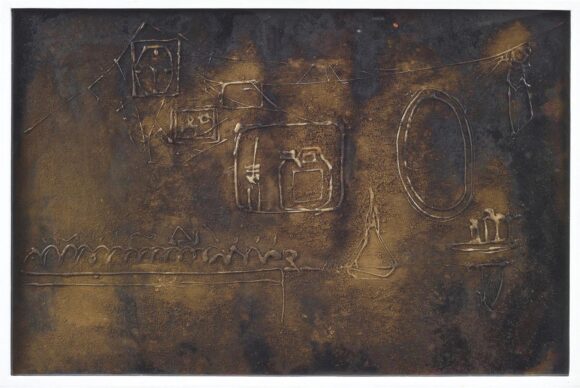

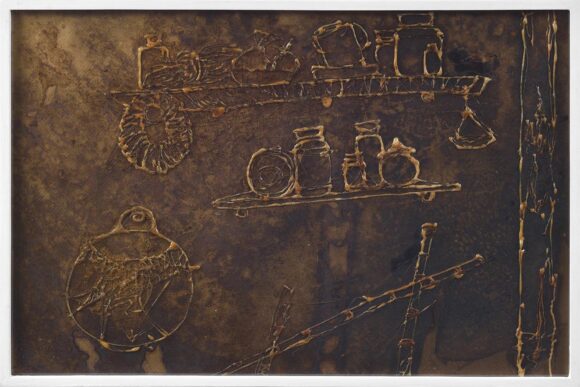

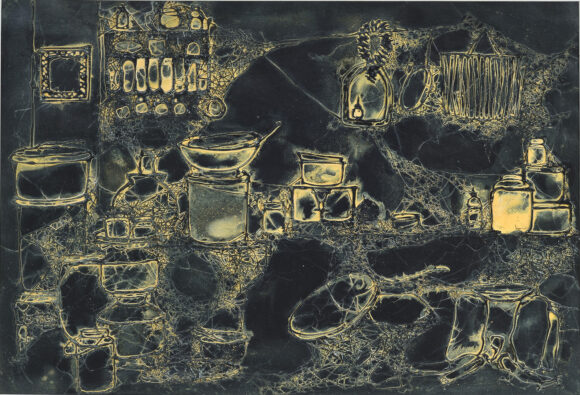

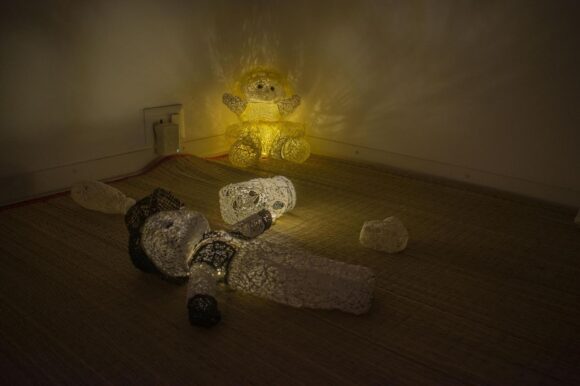

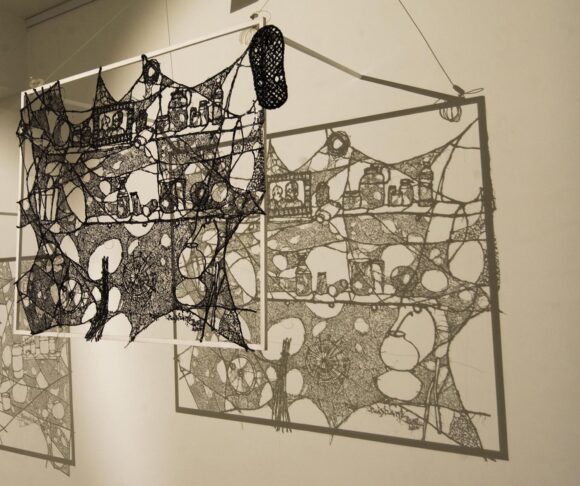

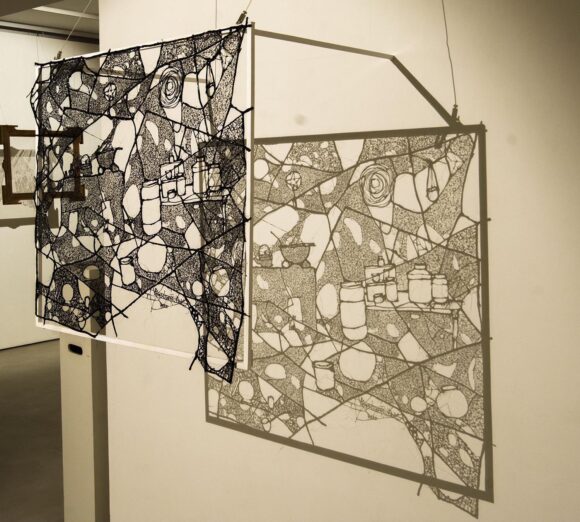

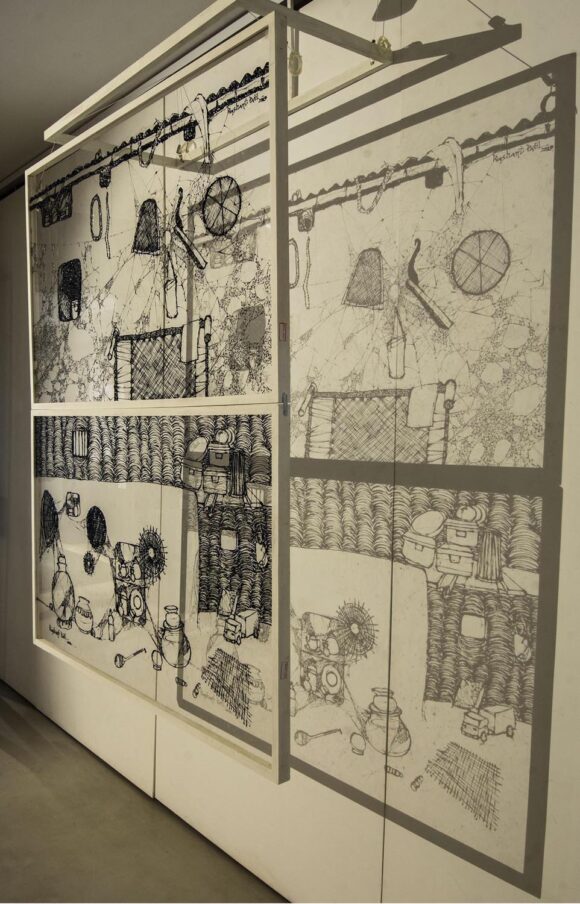

Patil’s world is a web of ephemeral lines and shadows – his world of memories, dreams and existential experiences intertwine to create strange, delicate, lacy three dimensional structures – sometimes balanced precariously and other times captured within frames and occasionally distributed on paper. His fleeting glimpses of life are first captured through complex drawings with glue sticks, solidified and then transformed into magical three dimensional installations, conjuring a shifting dreamworld, ever haunting and mesmeric!

On behalf of CIMA, I feel extremely honoured and happy to celebrate the emergence of a brilliant talent. May his thousand dreams bloom.

Rakhi Sarkar

Director, CIMA – Centre of International Modern Art

April, 2020

A Choreographer of Shadows

Evanescent memories; penumbral residues coating derelict corners.

Twilight creatures, shadows – wrought of lumos and umbra.

Appended, conjoined, in an infinite dance to the end of time.

Encountering absences

Prashant Shashikant Patil choreographs shadows.

Shadows, as elusive memories, inhabit his works; metaphorical, at times physical, or perhaps both. Why shadows? What do they mean to him personally?

Patil grew up in a small town in Koregaon, Maharashtra, a place where his parents still reside. A peri-urban township indistinguishable from hundreds such scattered across the Indian hinterland, forever poised between the pull of its rural roots and the promise of upward urban mobility; joined to their big-city cousins via mobile phones and cable TVs. Narrow bylanes, cramped houses, low roofs, big dreams and small opportunities that cause mass migrations throughout the country. This familiar subtext also runs through Patil’s journey. When he speaks of home and parents, the tug of an invisible familial umbilicus keeps him tied to his memories – memories as sticky as invisible spider webs holding him captive wherever he goes.

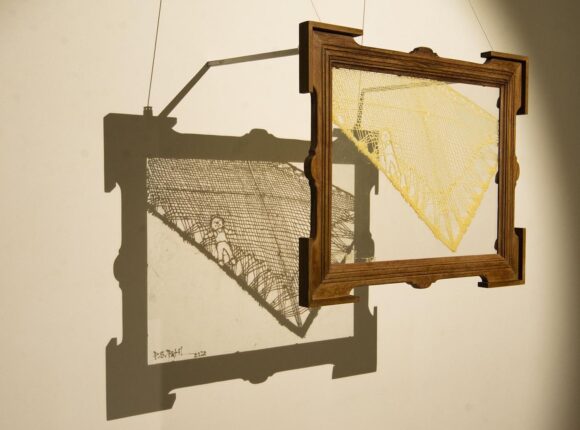

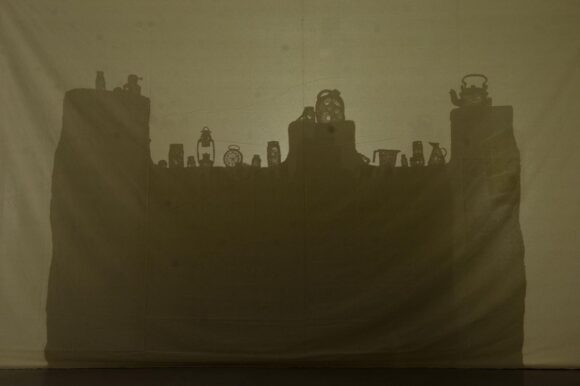

This emotional connection is the point of departure for a series which Patil embarked upon some years back while enrolled as a post-graduate student in Kala Bhavana, Santiniketan. While the physical separation between family and self, directed him to re-examine home/land and memory as persistent motifs, Patil was also faced with the dilemma of what methodologies might best capture the metaphorical distance between past and present into something tangible whilst appraising the indices of time as well. Hence, Patil created a series of works best described as filamentous sculpture-drawing installations, in which cast shadows becomes an indispensable element that intervenes between perceived and real spaces. This series won him the CIMA 2019 Young Artists award as well as a solo exhibition. Home lost, regained (lost again)

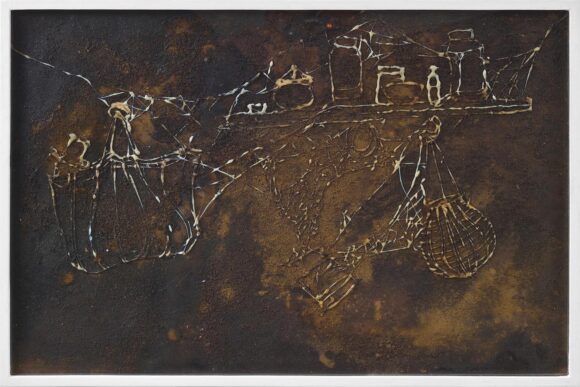

When Patil joined the painting department in 2016, he had carried with him a number of pen and ink drawings which scrutinized the rural-urban, human-mechanical binaries through humanoid robotic creatures, making these works an almost (post)human retelling of the Frankenstein myth which addresses larger more topical issues of what it means to live at the liminal boundaries of human and mechanical today, even as it raises questions of moral quandary. However, it is quite revealing that Patil chose to implant his cyborg creatures with objects taken from the surroundings of his home – metal buckets, kerosene lamps, iron well hoops, electric sockets. Apocalyptic images in art and cinema are usually a Western-urbanised rubric. Here, then something outside the norm happens – by using images of familiar daily use objects, the artist firmly puts his milieu centre stage.

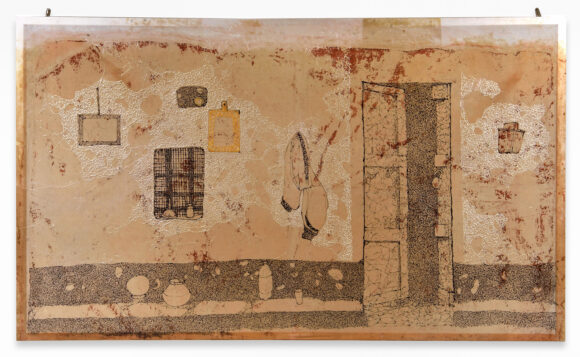

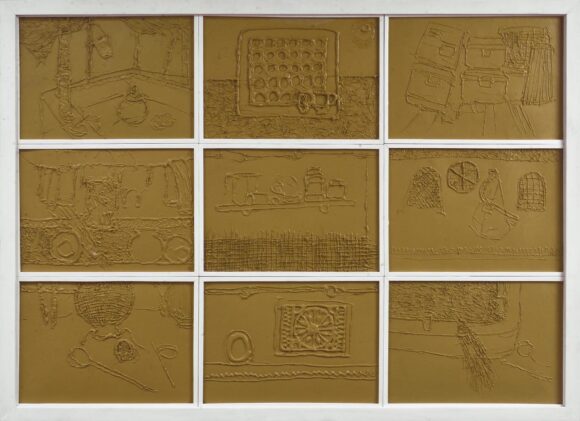

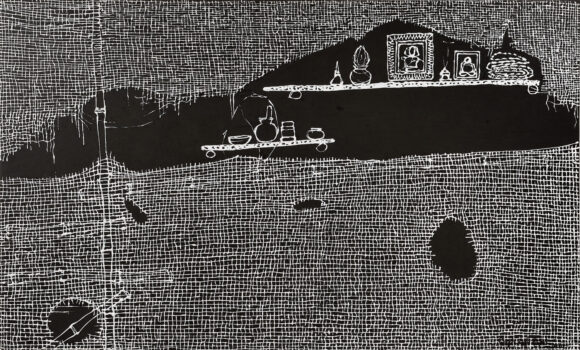

If the relocation to Santiniketan brought with it severance from the familiar, it had also introduced Patil to new visuals and sounds. He confesses to having never seen mud houses before arriving here. The unfamiliar surrounding that initially created a disconnect within him soon gave rise to a familiarity with rural imagery that has since, seeped into and firmly entrenching itself as a primary source for many of his works. This engagement may be equated with a yearning to cling on to what he describes as dying remnants of an endangered tradition. Patil’s intimate scrutiny of the tribal and rural communities in and around Santiniketan combined with a keen observation of its humdrum lifestyle has made him deeply cognizant of the attachment the under-privileged have for their few belongings which are reused and recycled till worn down and decrepit whereupon grudgingly discarded. The tossed-out trash and detritus, in many instances, sit in the immediate surroundings of the houses, shrouded in debris, dust or wilderness – images of uneasy truce between the natural and artificial. Without an overtly political stance, Patil manages to accentuate the influence of scarcity narratives on the environment. Furthermore, in ascribing these objects with characteristics of their human owners, Patil lets objects such as hurricane lamps, old plastic containers, tattered jholas and plastic bags hanging from rusty nails push out the human image from his work completely, turning household spaces and objects into allegories of impermanence and transience.

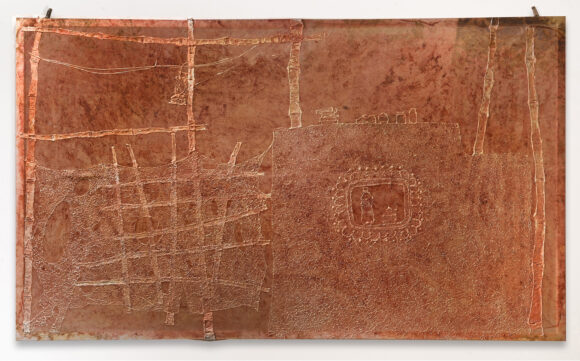

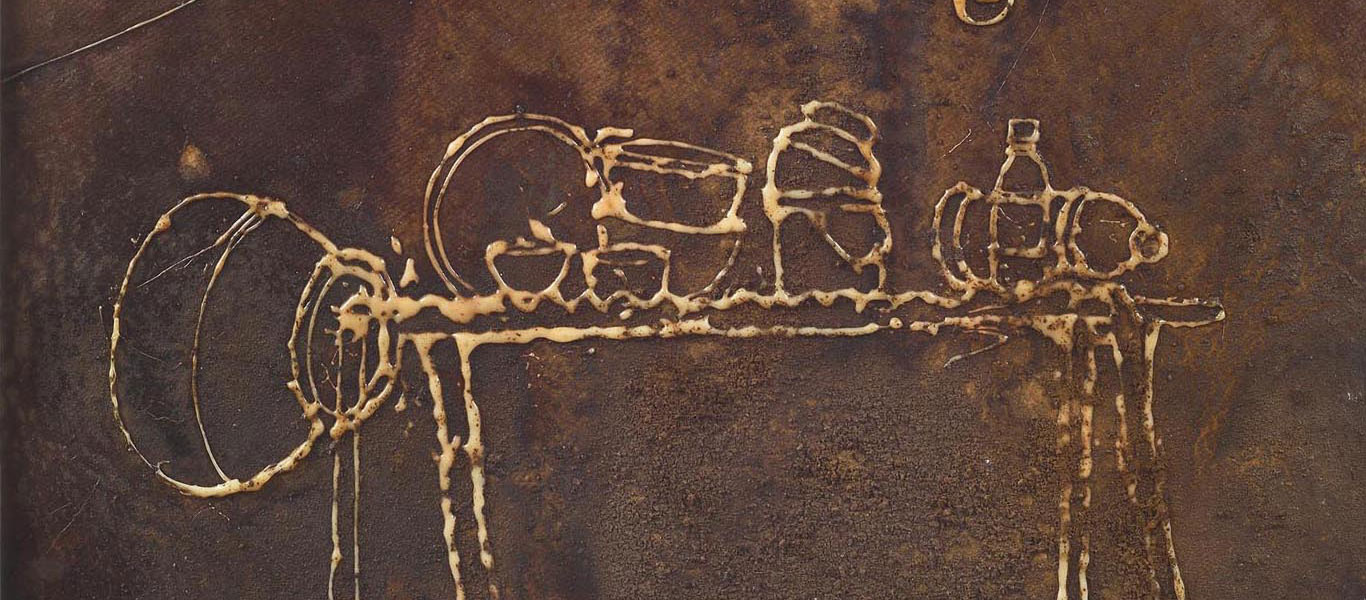

Around the same time, Patil felt a necessity to sculpt, to create objects that could exist independent of the canvas or paper and still retain the freedom of his drawing practice. This desire to shape the familiar into a three-dimensional form, but unfamiliarity with modes of sculpting, pushed him to find innovative tools. He tried using wire, however, was dissatisfied with the stiffness of the material. What began as a playful exploration of that ubiquitous medium of all self-help tutorials on You-Tube – the hot glue gun, slowly turned into scrawls and drawings on paper. The glue drawings produced a braille-like, smooth, raised surface which could be ‘read’ with fingertips. Experimentations from the time include drawings on canvas and paper using hot glue, combined with natural dyes or mud sourced from nearby villages. In some works, dust accretion was also adapted into the art-making process. Many artists have used dust as a material and metaphor to allude to the passage of time, of wearing away, loss and destruction; this preoccupation with immateriality creates an interesting perceptual shift within Patil’s works generating an area of flux or in-betweenness, where memory negotiates with time and space.

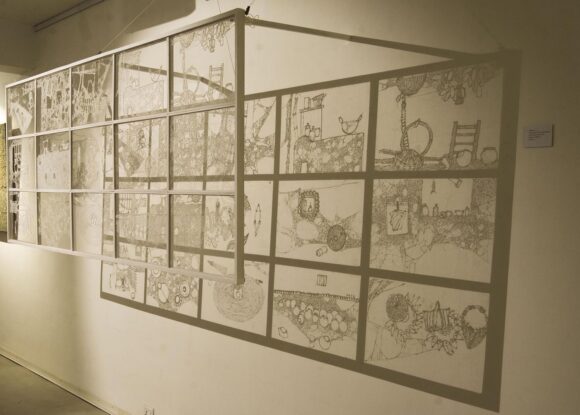

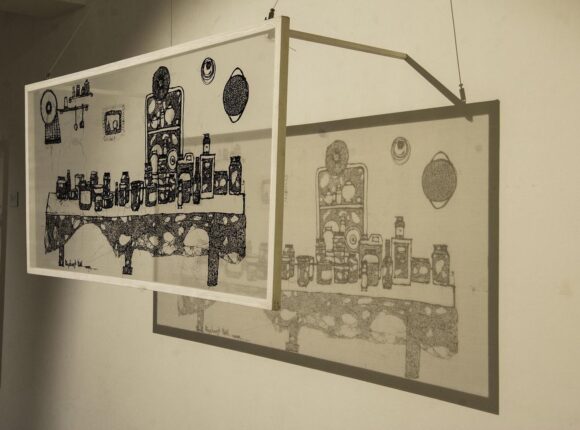

Eventually, Patil was able to, quite literally, extract his linear drawings out of the canvas or paper backing into delicate ‘drawing- sculptures’ existing independently in space. His chosen mediumhot melt adhesive also known as hot glue is a form of thermoplastic adhesive. The glue which is tacky when hot, sets rapidly to a pliable yet rigid material, thus allowing Patil the freedom to create spontaneous enmeshed networks of glistening strands suggestive of cobwebs. Patil speaks of cobwebs and his shadow casting drawings, and how the former inspired the latter. Once these ‘drawing- sculptures’ dry, they can be draped and displayed like lace or fabric. Despite the appearance of easy fluidity, Patil professes the process is time-consuming and gruelling. These diaphanous, free-flowing, traceries of overlapped cross-hatching, tenuously held together by the virtue of the medium, allows Patil to play with visibility and invisibility. In addition, by divesting these works of traditional methods of display, the image is transformed into an object. More importantly, when Patil introduces light as a vital element into the equation, he initiates a symbiotic exchange between object and shadow.

Seeing in the Dark

Returning to the question I posed at the very outset –

What meaning do shadows have within Patil’s practice?

In nature, shadows are tied to the movement of the earth relative to the sun, hence the notion of temporality is inherently embedded in shadows. Introduction of light in a work of art effectively raises some very interesting challenges. What I find of particular significance is the way shadows explore dimensionality as well as the fact that they create interstitial tactual spaces; spaces that exist only in relation to the other variable – light. Following this line of thought, where then, does the work begin and end? Where is the inside or the outside located? Does the artwork then consist of both the object as well as the temporary experience of light and shade?

Patil’s intricate illuminated drawings of private spaces and household objects from villages, talk about transitory human relations and loss on one level, but they also draw attention to metaphors of ignorance and fear of the unknown and binaries such as illumination and darkness, black and white, good and evil, past and present, impermanence and permanence. The installations suspended in mid-air, project intricate, active shadows that sway and animate; shadows that stretch into space, effectively multiplying and enlarging Patil’s drawings. Hence, it is not wrong to postulate that here shadows are central to a viewer’s experience. The viewer, free to move, in and around the works, becomes a participant by blocking and/or creating new permutations of shadows that play the dual role of a physical element that can be manoeuvred, but also one that is experienced psychologically.

Prashant Patil’s first solo collates a substantial body of work he has been working on for the past year. Patil is a talented young artist exploring new materials and concepts. In his shadow cast works he is able to raise critical queries about ephemerality. By contextualising everyday events into spatial/temporal experiences, Patil’s work also falls within registers of contemporary practices that investigate space as an important element of cognitive memory.

Patil has completed his Master’s degree in Painting from Kala Bhavana Viswa Bharati University in 2018 and since then has exhibited his works in several exhibitions across the country. He has also completed a year-long residency at Vis a Vis art studio in Vadodara and was part of a group show at Kochi Biennale collateral event in 2019. At present, he has returned to reside and work in Santiniketan.

Catalogue essay by Ushmita Sahu

Ushmita Sahu is a visual artist, scholar and independent curator based in Santiniketan West Bengal, India. She has numerous shows and projects to her credit. Sahu is a recent recipient of the IFA (India Foundation for the Arts) research grant. Recently she has curated IMPRINT: Riten Mozumdar at Chatterjee & Lal Mumbai in 2020.

STAY CONNECTED

Subscribe

Receive e-mail updates on our exhibitions, events, and more: