Silent Vision – Works by Suman Chandra

CIMA Award winner 2022

Opening 29 July, 6 PM

29 July – 19 August 2023

CIMA Gallery

Kolkata

Foreword

Suman Chandra is the winner of the fourth edition of the CIMA Awards. A young artist hailing from the semi-urban outskirts of Bengal, Suman completed his Master of Fine Arts degree from Kala Bhavana, Visva Bharati University, Santiniketan.

We are indeed fortunate to have discovered Suman. I am personally grateful to each and every member of the juries who shortlisted and finally awarded him.

Suman is principally engaged with the devastating impact of coal mining that affects the lives and destinies of innumerable helpless people trapped in a destructive chain of events, leading to unimaginable environmental hazards. His art itself becomes a symbol of that vicious disaster and pathos, though it is expressed subtly, with beauty, artistic skill and deep empathy. His art is a silent reminder of Man’s ravages against Nature and, ultimately, his own destiny.

On behalf of CIMA and the members of the jury, I wish him a successful future.

Flickering Lights and Dancing Shadows

by Siddharth Sivakumar, Head Visual Arts & Publishing, Kolkata Centre for Creativity

Coal has played a vital role in India’s industrial development and currently satisfies 55% of our energy requirements. However, the coal sector has also been a subject of contention. In 1971, coal mines were nationalised to align them with national priorities and address social concerns. Although this move contributed to achieving national self-sufficiency, it did not completely resolve the social issues associated with the industry.

In 1994, Coal India Limited released a statement known as the Coal India Resettlement and Rehabilitation Policy for people displaced by mining activities. In the ensuing discussions and debates, it became clear that the personal choices of the marginalised were outweighed by the ‘National Interest’. Writing about ‘Coal Mining Displacement’, Justice Ratnaker Bhengra writes, “Indeed, the weakness of the CIL’s rehabilitation effort is its consistent refusal to face evidence that mining displacement is causing structural violence to the weaker sections, that it is violating their basic human rights, that it is creating a massive transfer of resources from those who have little to those who already have much, and is causing the political, economic and social marginalisation of people”. The self-employment programs and diary-poultry production schemes were floated as part of the rehabilitation process while incentivising NGOs working for the welfare of the mining workers. However, quickly turning unskilled, illiterate people with the necessary technical, managerial, and marketing skillsets into self-sustaining entrepreneurs was an unattainable goal.

Despite increased investments in infrastructure, education, and healthcare, mining workers continue to face exploitation and low wages. Another significant challenge lies in the rehabilitation of affected individuals. Despite tribal people constituting only 8% of the population, they account for 40 to 50% of those displaced by mining activities, and their lives have not significantly improved despite various initiatives.

Furthermore, the privatisation of mines has been reintroduced with some modifications, further complicating the situation. On March 29, 2023, the central government announced the 7th round of its coal mine auction, which contains 101 mines, including Tara block in Chhattisgarh’s sprawling Hasdeo Arand forest of 1,70,000 hectares that is home to a diverse ecology and tribal communities such as the Gonds. As a result of the latest phase of privatisation, according to the official estimates of Odisha, Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh, close to 20,000 families would be uprooted from their homes. To see the numbers in the right context, one only needs to read Coal India’s ‘Business Responsibility and Sustainability Report’ (FY 2021-22), which states, “In line with our commitment to the various displaced people, 1545 land oustees were employed at CIL during FY 2021-22”. Similarly, discussing its ‘Rehabilitation and Resettlement’ policy, the report highlighted Coal India’s ‘Singrauli Women Small Holders Poultry Project’. It claimed, “Presently 584 [poultry] units have been constructed, while 166 beneficiaries have been identified for inclusion”. Research indicates that around 200,000 people have been displaced solely in Singrauli due to dam/reservoir, thermal power, and mining projects. When considering the deficiencies in compensation and the loss of subsidiary livelihood sources provided by forests and rivers to the original inhabitants of these regions, the impact becomes even more profound. But what happens when an artist approaches the dark realities of the necessary evil, the coal fields?

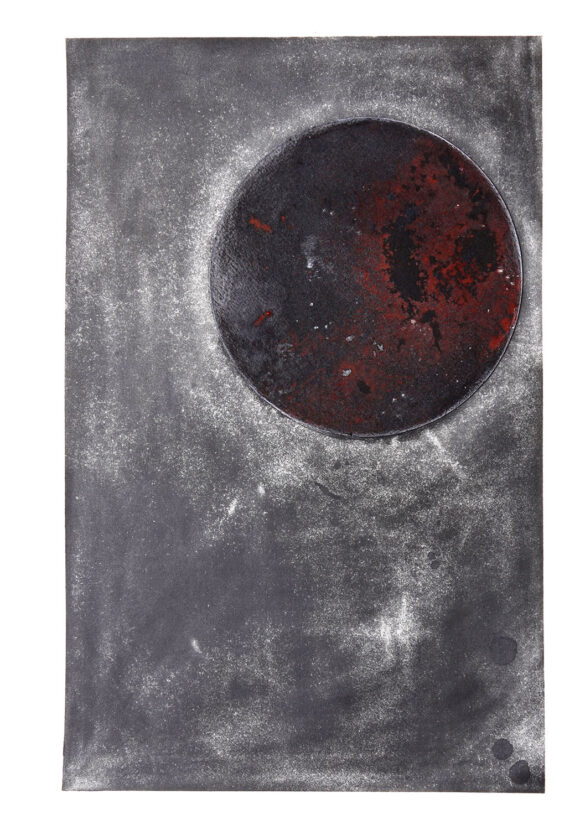

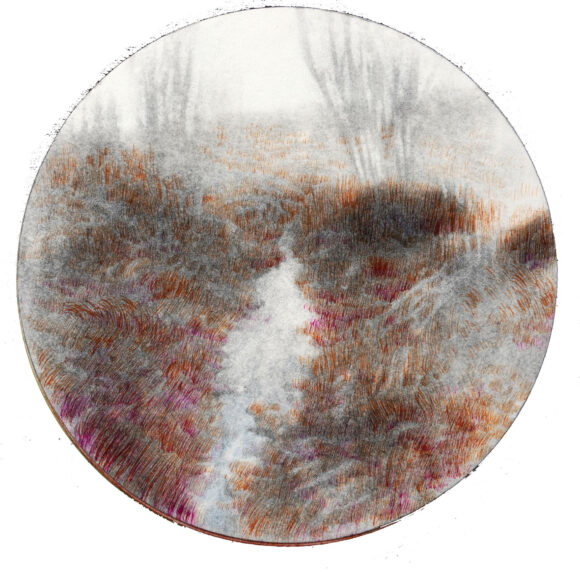

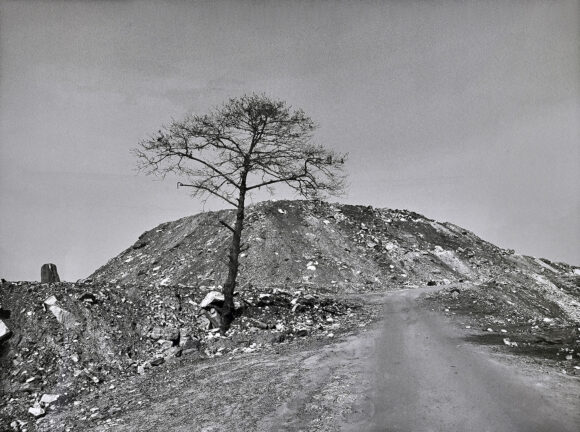

The materiality of coal mines as landscapes, and miners involved in a dangerous yet captivating occupation serve as the inspiration for Suman Chandra’s artworks. Over his half a decade of research activities in mining areas, partially funded by Kolkata Centre for Creativity’s Fellowship program, he attempted to understand the ground realities and respond to them artistically. Viewing the world through a coal-filtered lens, Suman connects the material with various facets of life. Initially, the visible surface features in coal mines fueled his artistic endeavours. However, as he explored further, his focus expanded to include the human lives intertwined with these mining landscapes. Coal, prized for its economic value, becomes subject to various forms of control and manipulation for monetary gain. The lives of those entwined with it, particularly generations of coal miners, experience fluctuations due to political decisions and policy paralysis. Suman, the son of a coal seller from Midnapore, makes a deliberate choice to depict the dark imagery of coal mines through his paintings. Despite knowing its intrinsic value, Suman’s upbringing allowed him to experience the stigma surrounding coal intimately. The early influence of his father’s occupation deeply shaped his perspective. Through his artistic vision, Suman aims to increase awareness, challenge existing perceptions, and ignite meaningful conversations about the social, economic, and ecological aspects of coal mining. His creative practice serves as a potent tool for fostering understanding and introspection, prompting viewers to reflect on the complex realities associated with the industry.

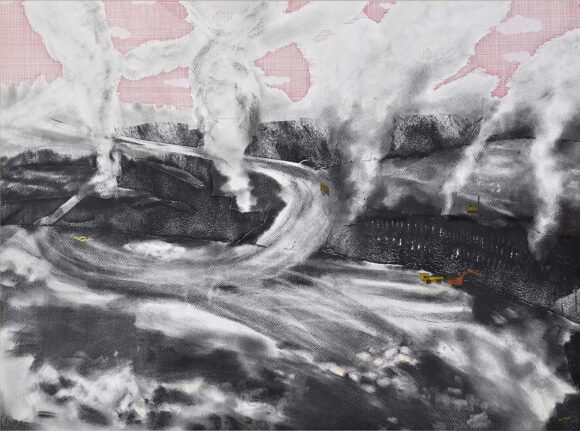

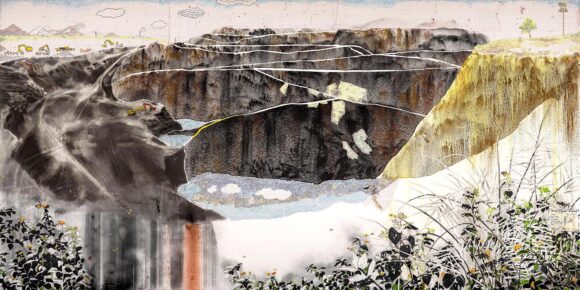

For land to be known as a landscape, it has to retain a certain experiential independence through its vast barrenness, beauty, wilderness, or any of its other inherent qualities to the person exploring and appreciating it. In other words, when a land’s salient features—hitherto beyond the scope of the observer’s mundane experiences—are encountered for the first time, it triggers an aesthetic response in the viewer that bestows on the land characteristics of a landscape. The colossal coal mines of Suman’s paintings qualify as landscapes, for they too fall far beyond our mundane experiences.

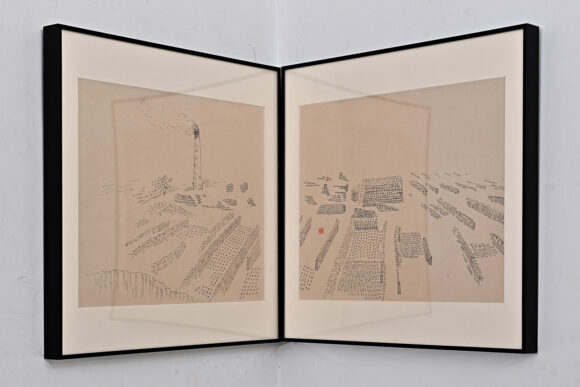

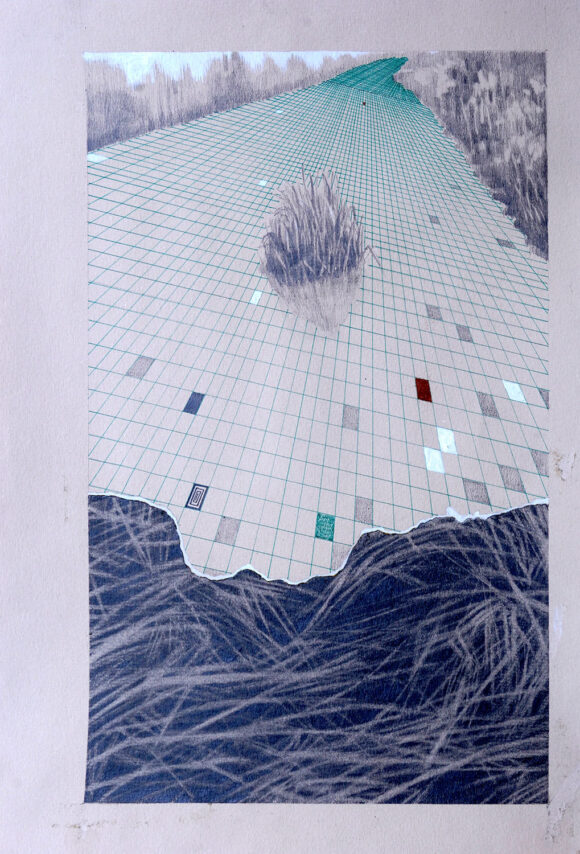

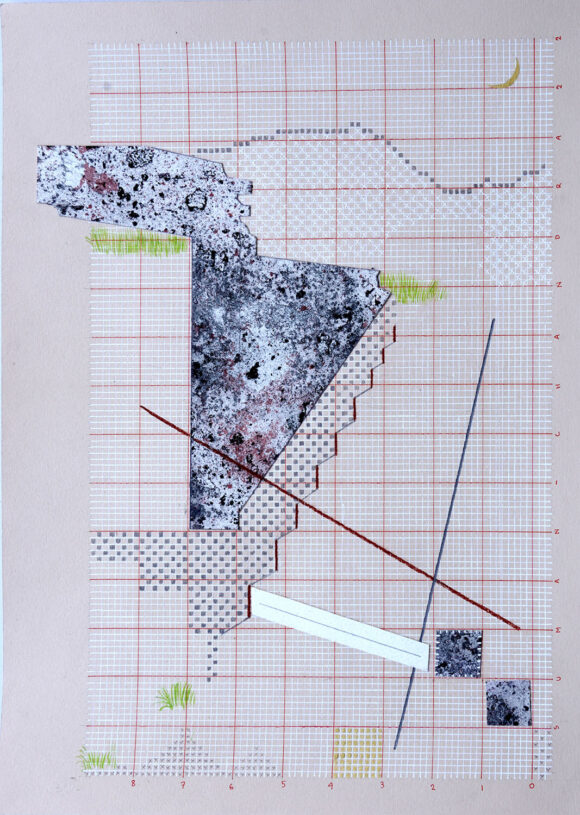

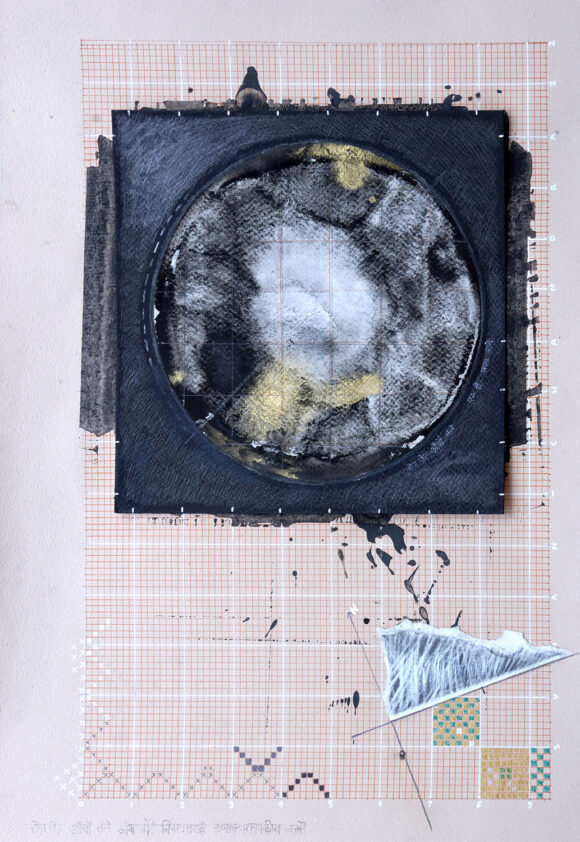

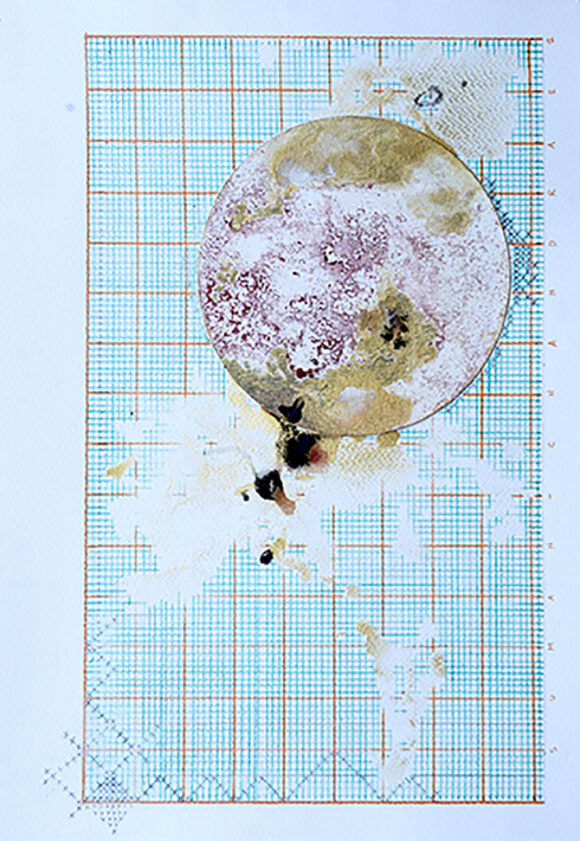

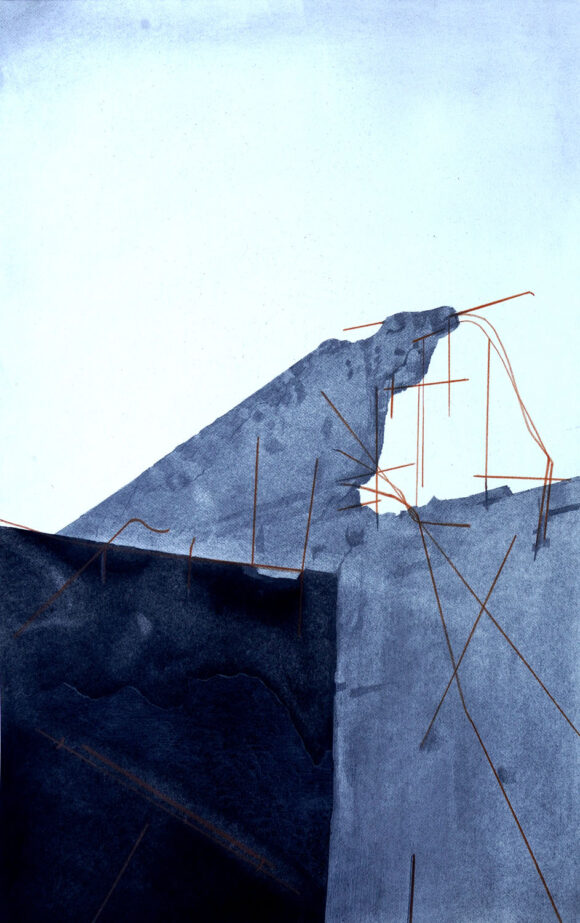

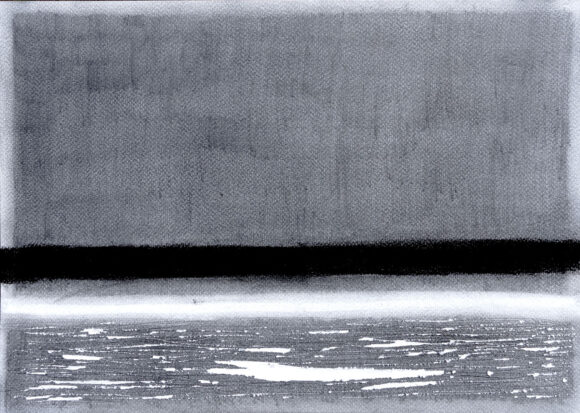

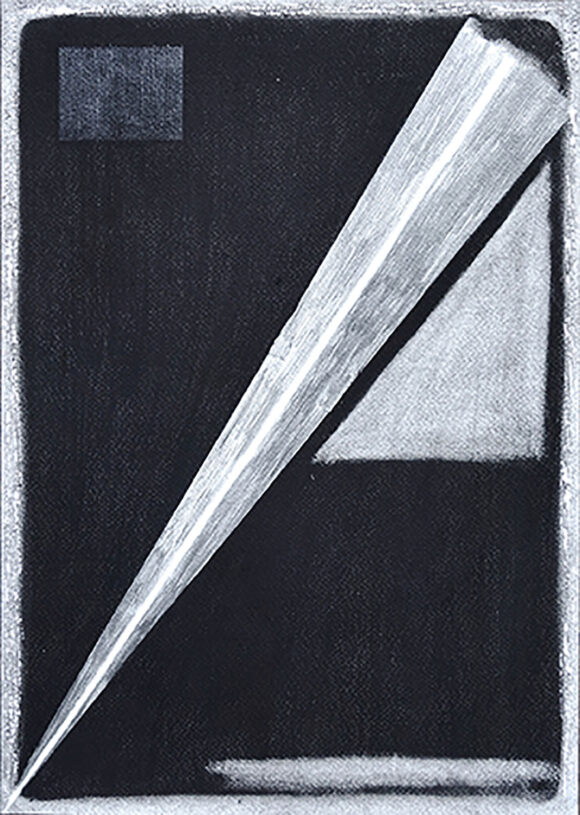

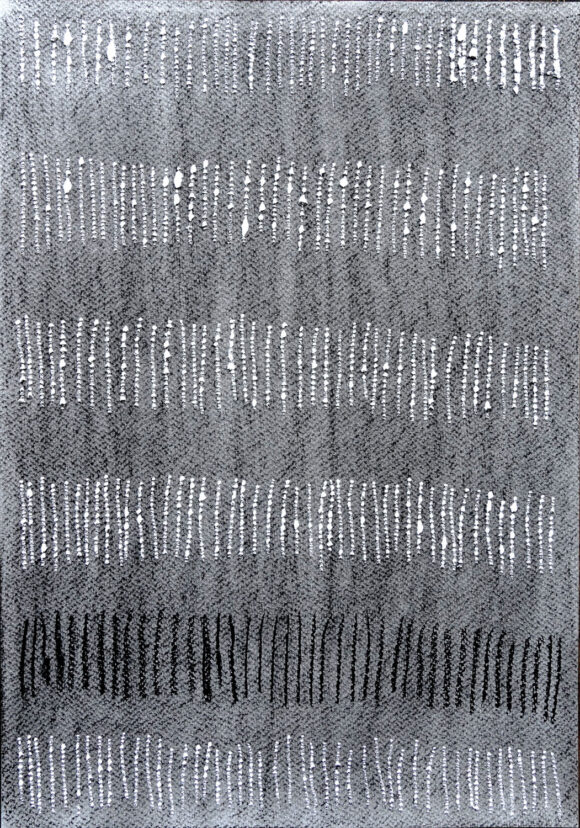

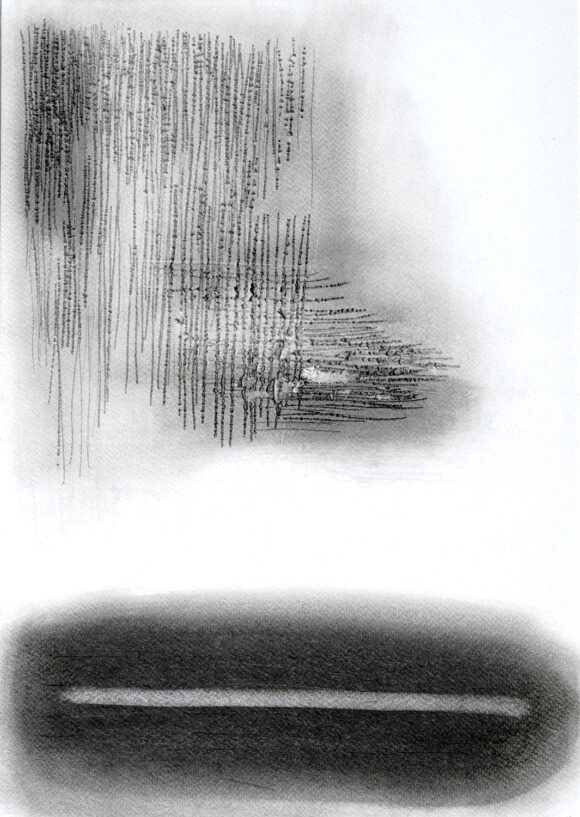

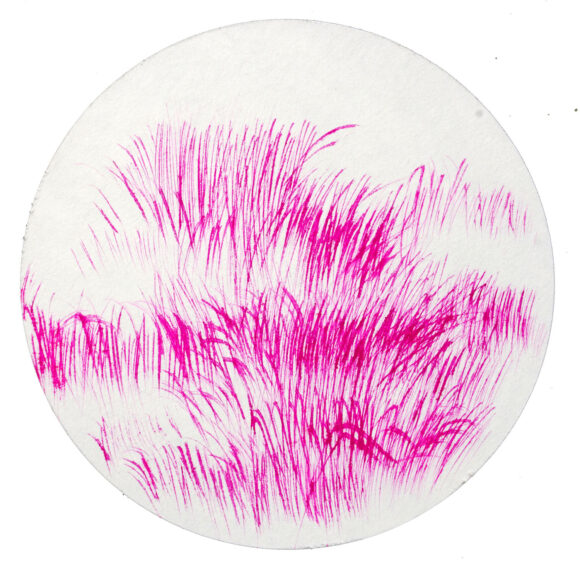

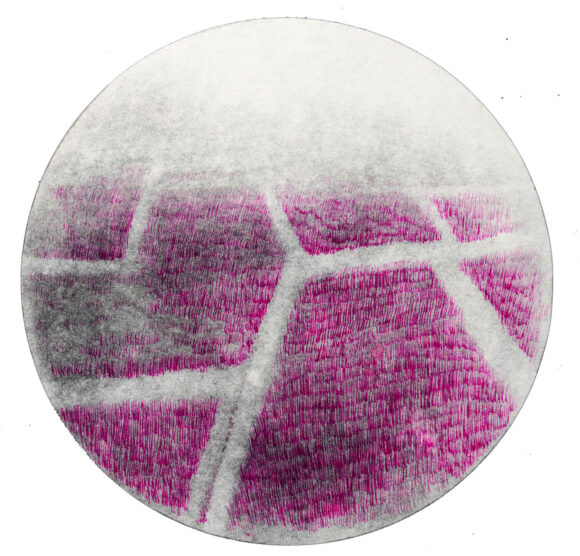

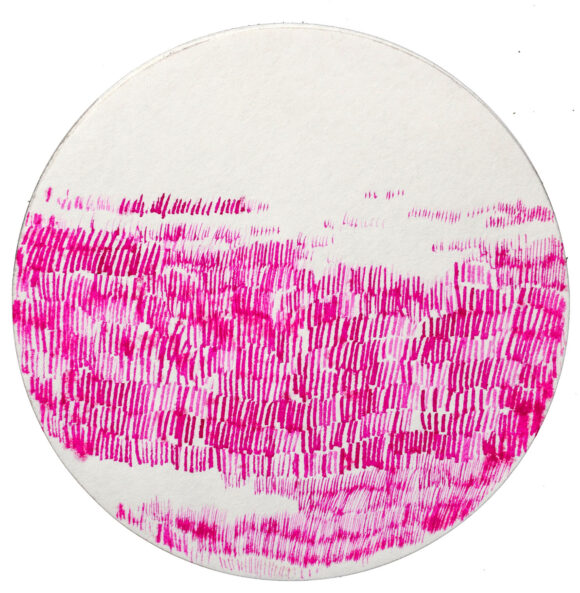

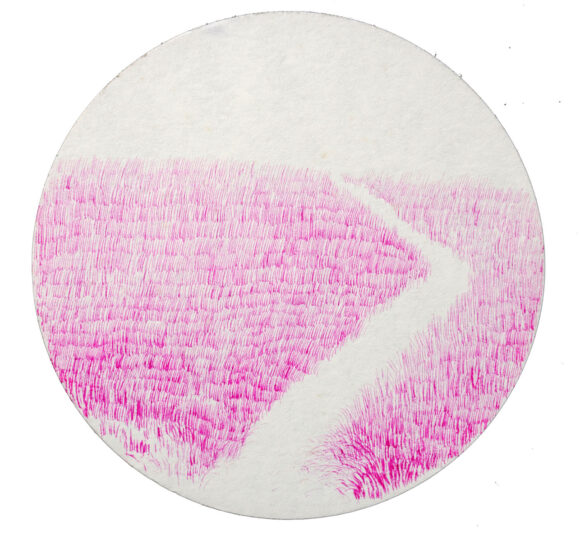

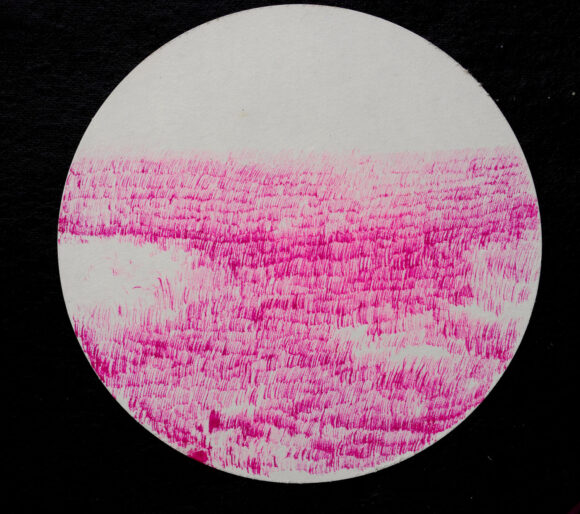

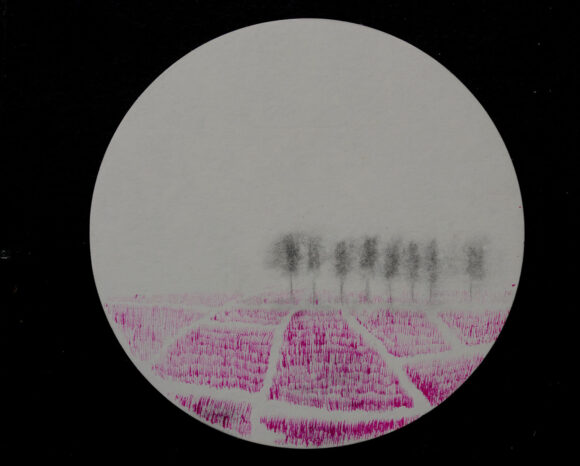

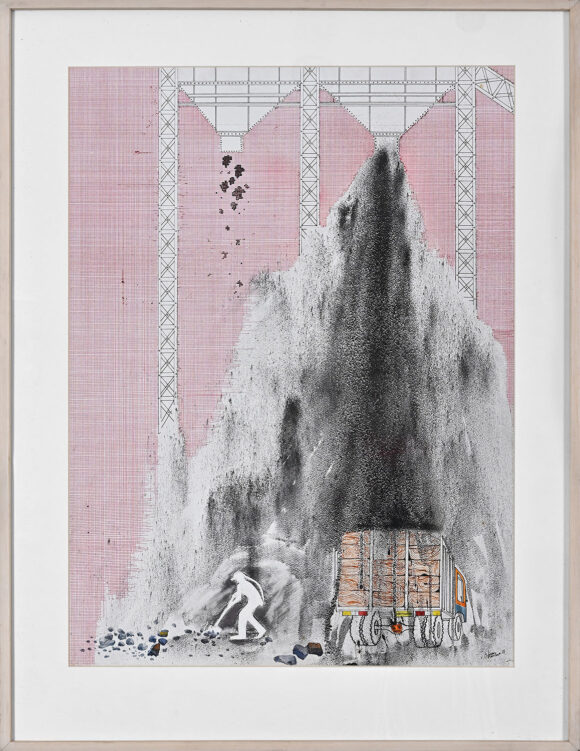

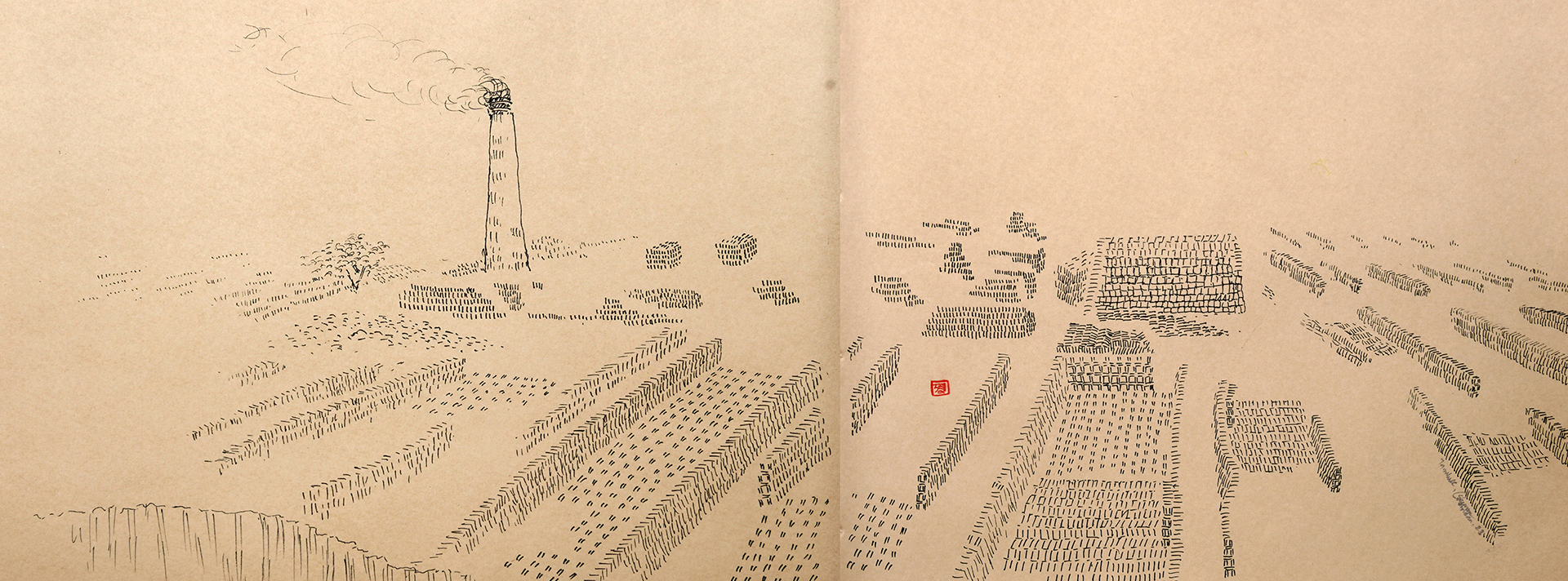

The land formations that inspire him, however, result from man’s manipulative tendencies. One might call it a ‘landscaping’ exercise that has not only abandoned aesthetic considerations but continues to cause environmental issues and health hazards in lieu of mining profits. However, land cut and carved out into neat landscapes for mining is not landscaping but sheer exploitation that fuels the growth of coal organisations and the nation. In his paintings, Suman engages in a pictorial ‘landscaping’, where unpalatable truths about man’s fragile existence at the margins of coal mines, and his dependence on the ever-expanding alienating land that keeps devouring and spitting him out like a giant whale, are balanced aesthetically—often using the engineering grids, representational maps and graphic conventions of collieries. In the mining areas, Suman has explored working blueprints of the collieries with dumping sites, stone layers and stagnant water, all marked with different manually filled patterns. This differentiation system to maximise extraction makes its way into Suman’s visual vocabulary. As the collieries are mapped with the pink engineering grids, within which lives are charted with healthy profit margins, Suman adds another layer, borrowing from his childhood’s multi-level Super Mario video games. Like in Super Mario, an ordinary coal worker operates across different roles and jumps through many hoops in the course of the day. Yet, at a deeper level, by using pixelated images where units do not come together to form a clear picture, Suman also reminds us of the inherent infirmity of the larger picture—the dysfunctionality of policies that fail to correspond to reality. In the backyards, hidden behind shrubs, rathole mining, which has been long banned, is still rampant as tunnels go deep into the earth, and men climb down illegally, risking their lives daily for a lump of coal. As the mines expand, men and children gather to break down abandoned houses—a brick at a time to earn a rupee per piece.

Interestingly, the human eyes horizontally cover roughly 180-degree of vision. But with its narrow lanes, bulging balconies, crowded streets and jarring highrises, the field of vision in an urban setting is often fractured into smaller compartments like a cubist painting. As a student of Kala Bhavana and a resident of Santiniketan, expansive unfurling landscapes, especially the starkness of the erstwhile Khoai landscape celebrated by the likes of Benodebehari Mukherjee, are not unfamiliar to him. In the larger works, Suman makes use of a similar visual device to recreate the manufactured landscape and the struggle of marginal men, who are barely seen and hardly acknowledged. In Suman’s expansive paintings, thus, the politics of land and the poetics of landscape painting find perfect synergy, where the imposition of an aesthetic framework raises questions of suspended ethics.

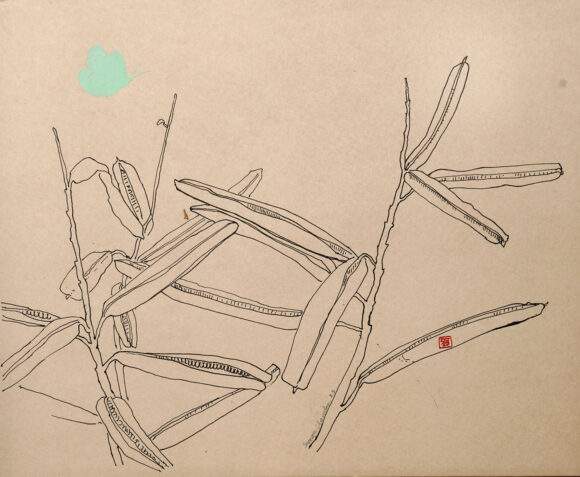

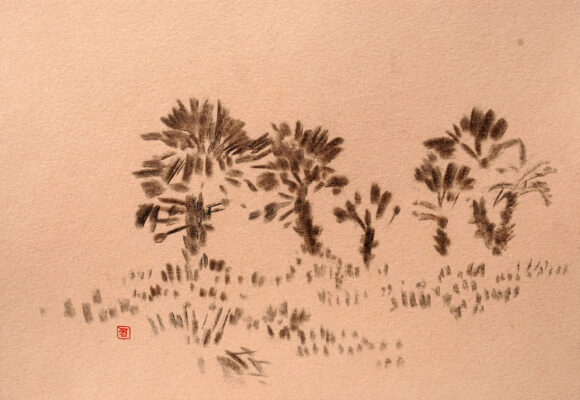

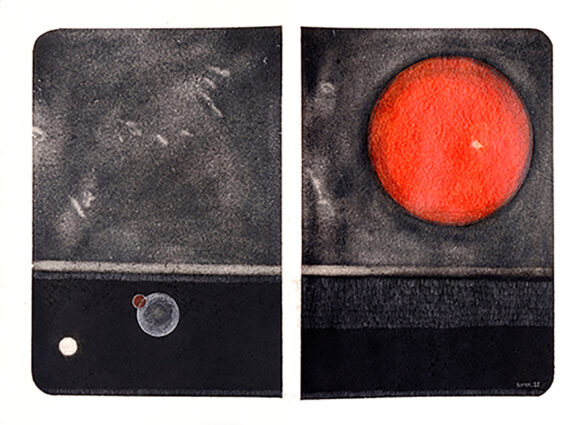

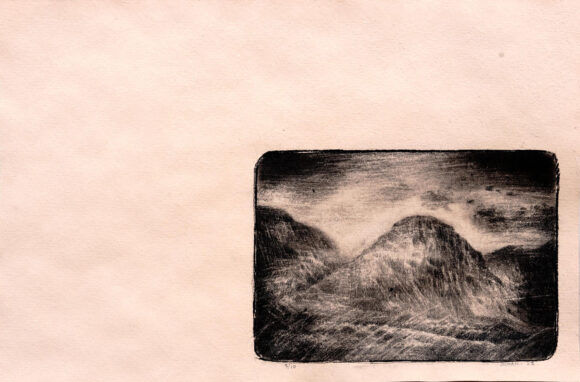

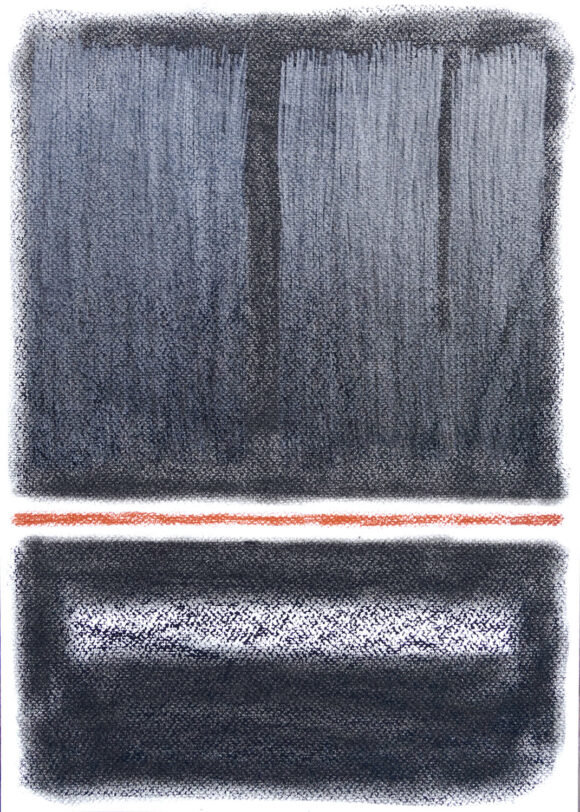

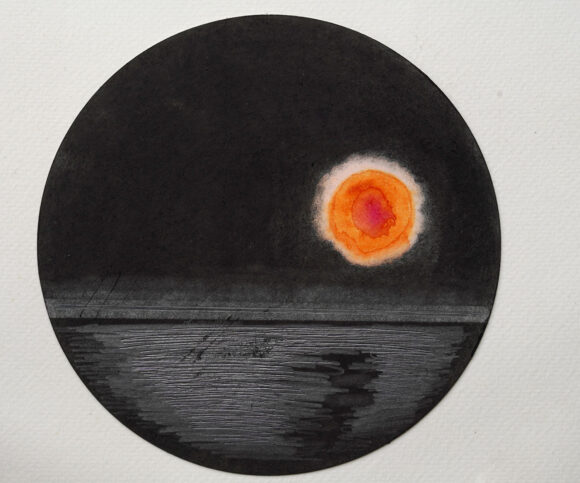

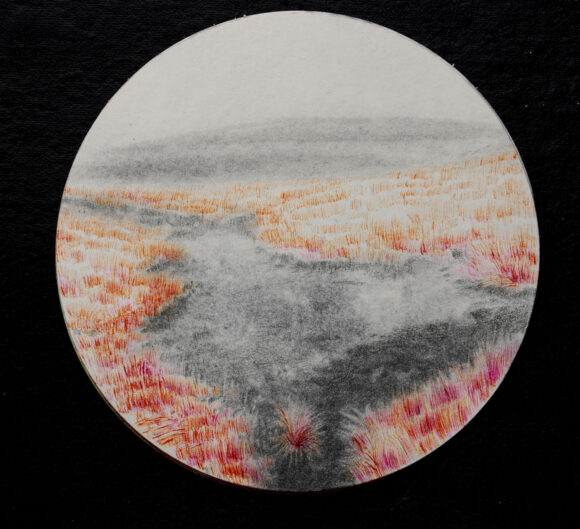

Interestingly, in July 2019, Suman visited the Basanti Mata Dahibari Colliery in Jharkhand, an experience that offered a fresh perspective on the hardships faced by coal miners and their struggle for basic necessities. This encounter sparked a newfound understanding of the daily challenges and realities endured by those working in the industry. In the mine and surrounding areas, Suman saw everyday activities unfold, young and the old crisscrossing nonchalantly the toxic fumes escaping from underground. On a rain-drenched afternoon, Suman felt as though he had come to Kashmir, heaven on earth, where clouds descended into the valleys. As Suman delved deeper into his project, his grasp of the material and understanding of life at the edge of the mining belt evolved, often finding expression through abstraction and a suggestive, minimalistic approach.

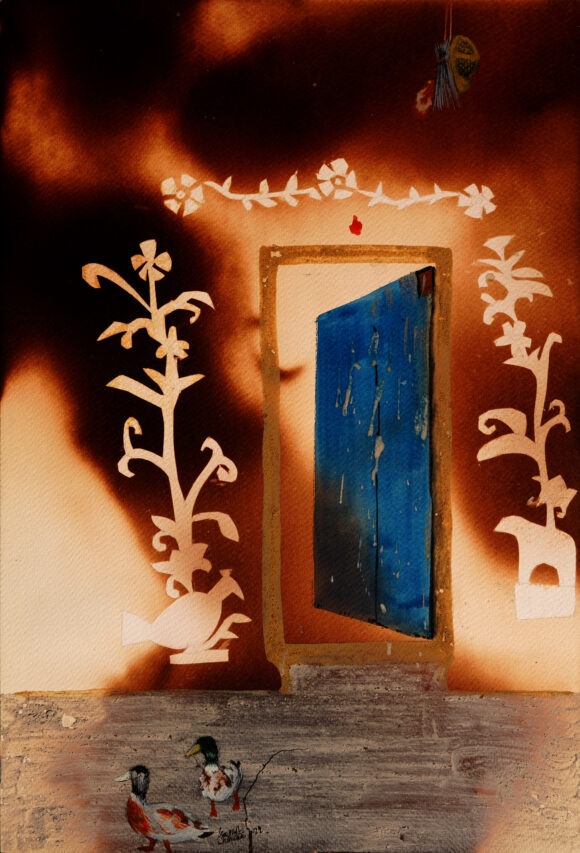

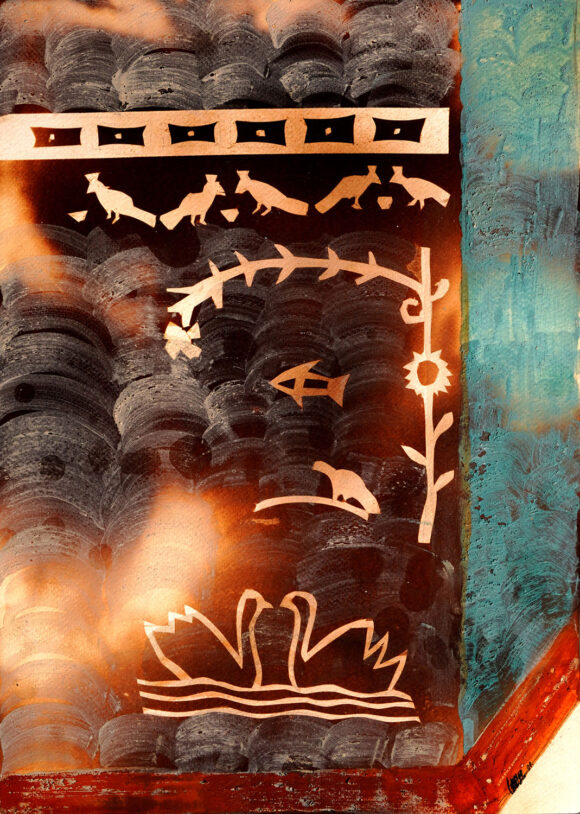

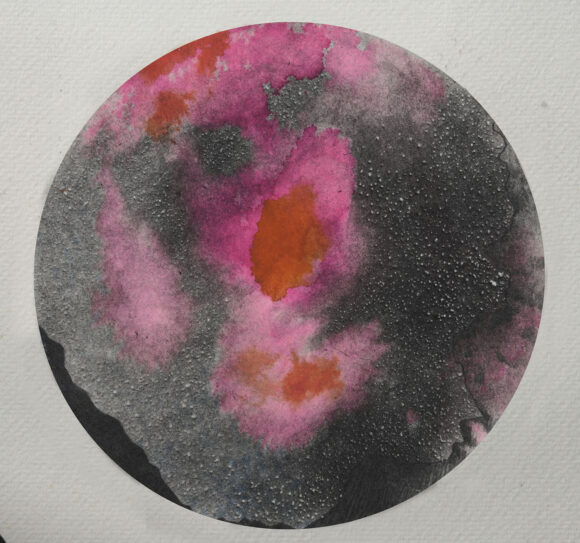

The current generation of coal miners migrated to Jharkhand in 1990, practising the traditional art form of Sohrai. This was the first time that, in the bosom of the dusky landscape, he saw traces of an artistic tradition. Originally prevalent in the border regions of West Bengal, Odisha, and Bihar, Sohrai had its roots in the Hazaribagh region, where artists used natural and mineral colours for their paintings. However, due to migration and land politics, Sohrai underwent changes in the coal mine areas. In some regions, relief Sohrai emerged, incorporating paddy grains to adorn mud walls. Unfortunately, the agricultural lands that were once abundant sources of grains and coloured soils, essential for the art form, have vanished. Today, Sohrai relies on synthetic colours readily available in the market. As a result, the present generation often covers the protruding palpable motifs of the older generation with garish artificial colours. Additionally, with the government providing living quarters, individual miner families seldom have their own mud houses, leaving limited space for decorative wall art.

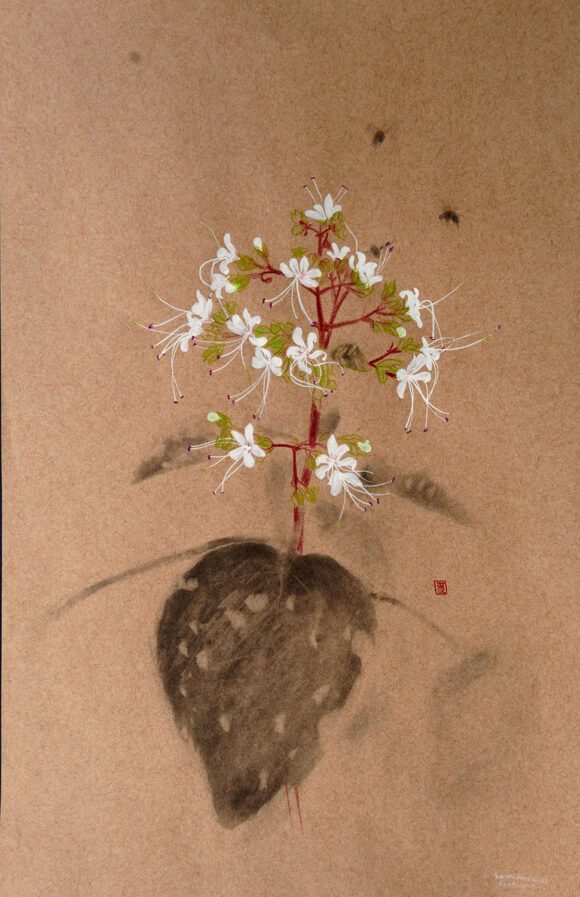

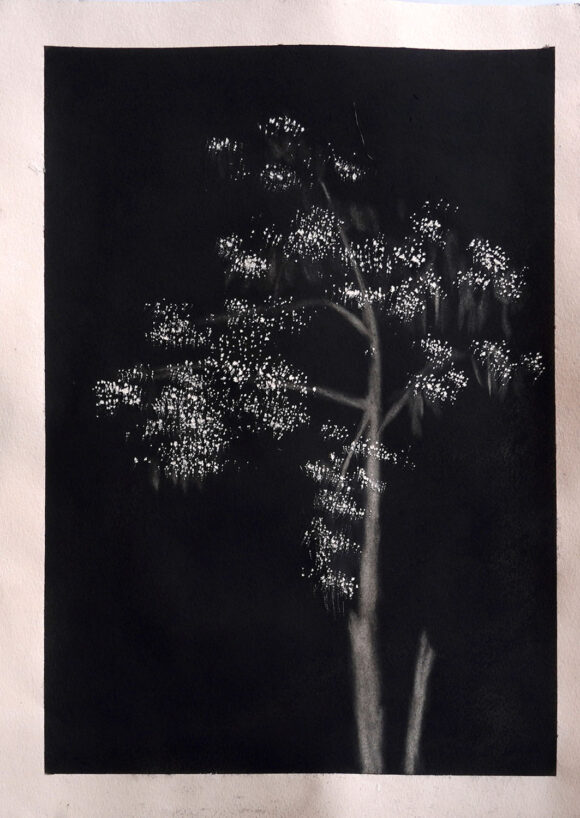

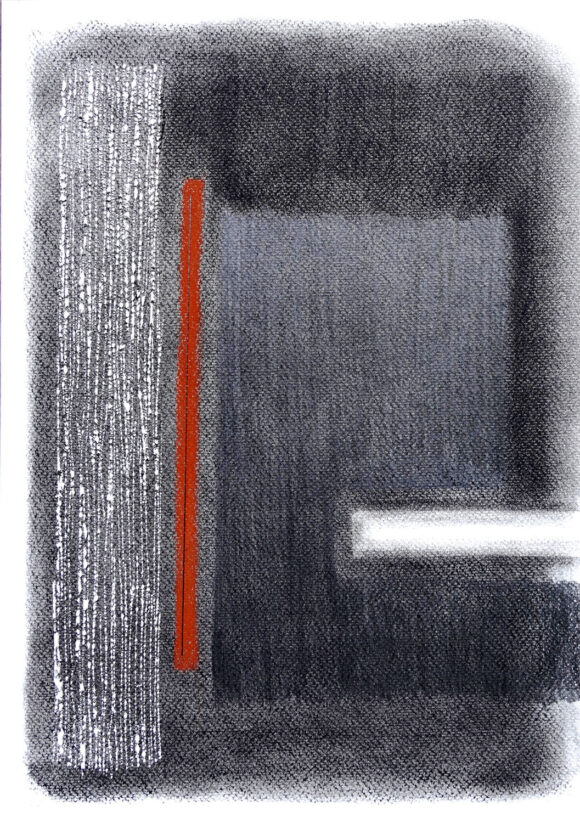

Suman innovates a process of image-making, carefully choosing traditional motifs from the disappearing Sohrai practice, turning them into stencils, and transforming them into archival artworks curing them under the toxic fumes. The effect is breathtaking as the image deceptively puts the onlooker at peace, calming the senses with what appears to be intimate slices of bucolic domestic life. While no man, woman or child is seen in these images, one notices ducks or goats playing by, a blue door ajar enough to seem inviting, and of course, the vanished Sohrai floral motifs illuminated on the walls. The soothing effect this set of paintings creates owes to the sheltering shadows that playfully envelop them. This layer, though has a dominant presence, is actually created by the biting scars left behind by the poisonous fumes. As Suman documents the Sohrai tradition and pays homage to the colourful people lost at the margins, he also reminds us of the ever-so-threatening darkness of the coal mines by infusing the methane and carbon monoxide fumes into the image-making process. The flickering lights and dancing shadows constitute wishful rural imagery. Still, awareness of the process forces one to mull over the flickering fire and suffocating smoke that spreads across the entire landscape, including the colourful skirts of the mines. This emotional paradox that the images trigger mimics the problems of mining policies and implementation dilemmas. In a work like Āẏōjana or Preparation, three strips come together, again focusing on separate realms that coexist, but often the interactions between them are strained by palpable tension. In this set, the realities are foregrounded, and the aspiration and dreams of the miners spread across the sky. Yet, the demarcating and all-determining politics rages on somewhere in the middle ground. These paintings take after the noted Bengali poet Srijato Bandyopadhyay’s Upanishad-inspired song Asato mā Sadgamaya/ Tamasomā jyotir Gamaya (Lead me from the unreal to the real/ Lead me from darkness to light), which hammers on people’s centrality in discourses and the validity of individual perceptions, quite like Rabindranath Tagore’s poem ‘Ami’ or ‘I’ from the poetry collection Shyamoli (1936).

In the grand scheme of things, it is only natural that Suman Chandra or Banka Chand (crooked moon), as his friends and peers fondly call him, invokes the sapient lines from Srijato Bandyopadhyay’s Bengali song, which echoes Suman’s sentiment and reveals where his sympathy lies. Roughly translated to English, the verse from Srijato’s song reads:

Look at the light in the sky,

Look at the sky full of stars,

Look at the way the wind is blowing madly,

All this joyous arrangement is in vain without me.